TL;DR :

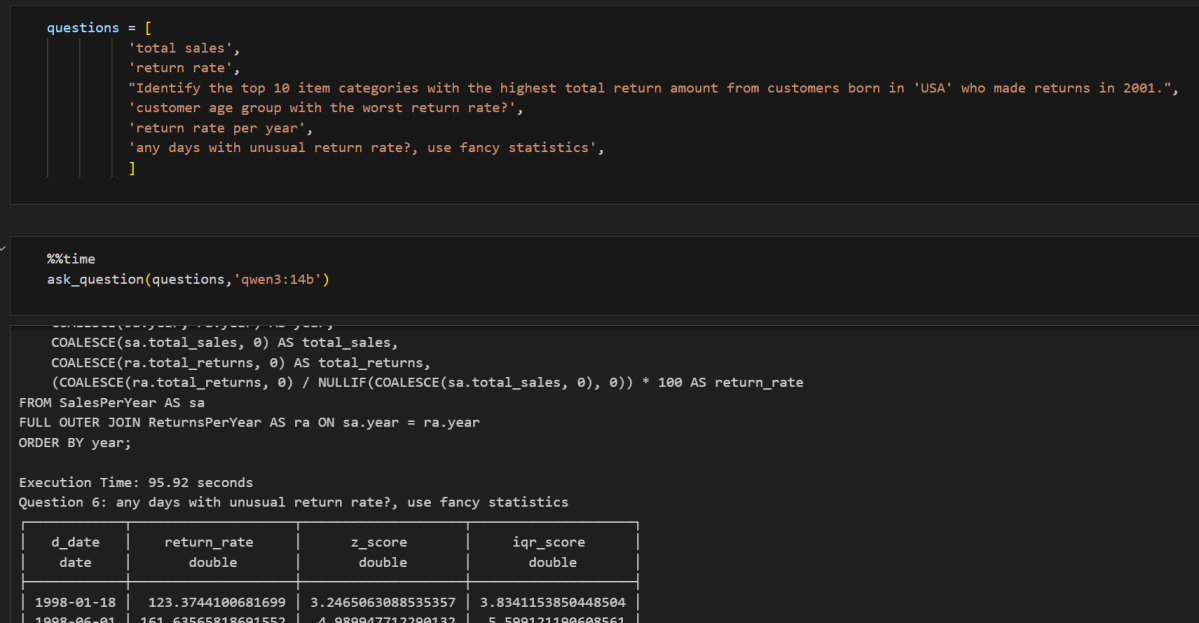

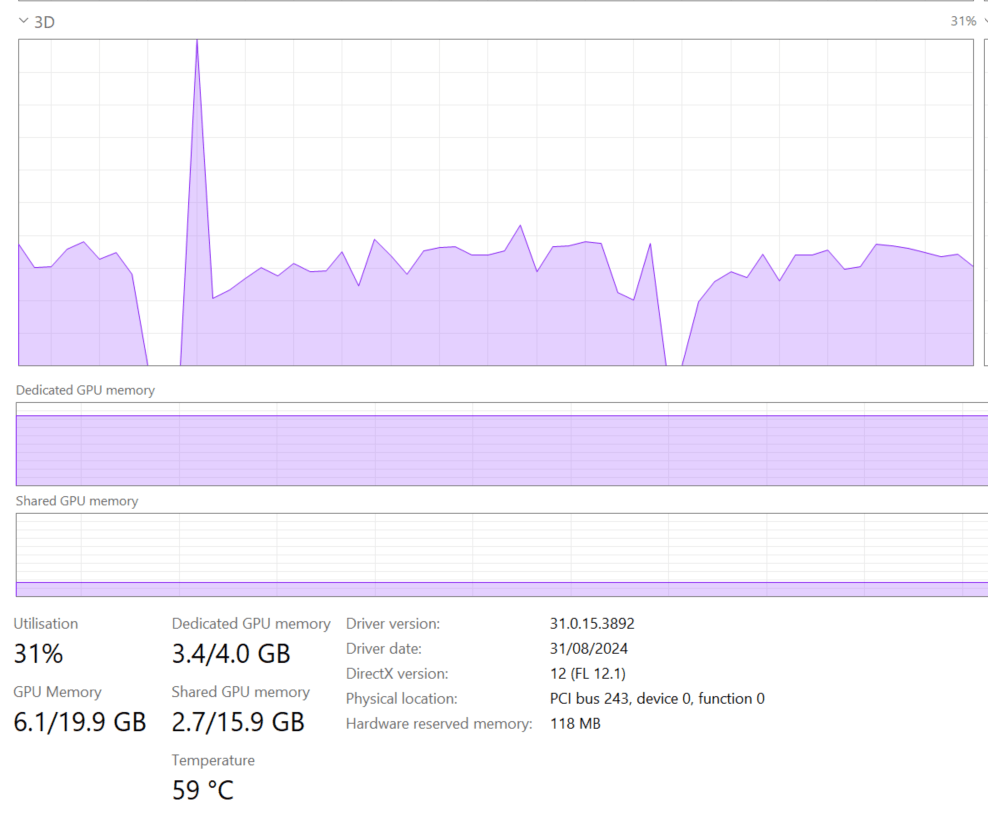

As a quick first impression, I tested Generating SQL Queries based on a YAML Based Semantic model, all the files are stored here , considering i have only 4 GB of VRAM, it is not bad at all !!!

to be clear, this is not a very rigorous benchmark, I just used the result of the last runs, differents runs will give you slightly different results, it is just to get a feeling about the Model, but it is a workload I do care about, which is the only thing that matter really.

The Experimental Setup

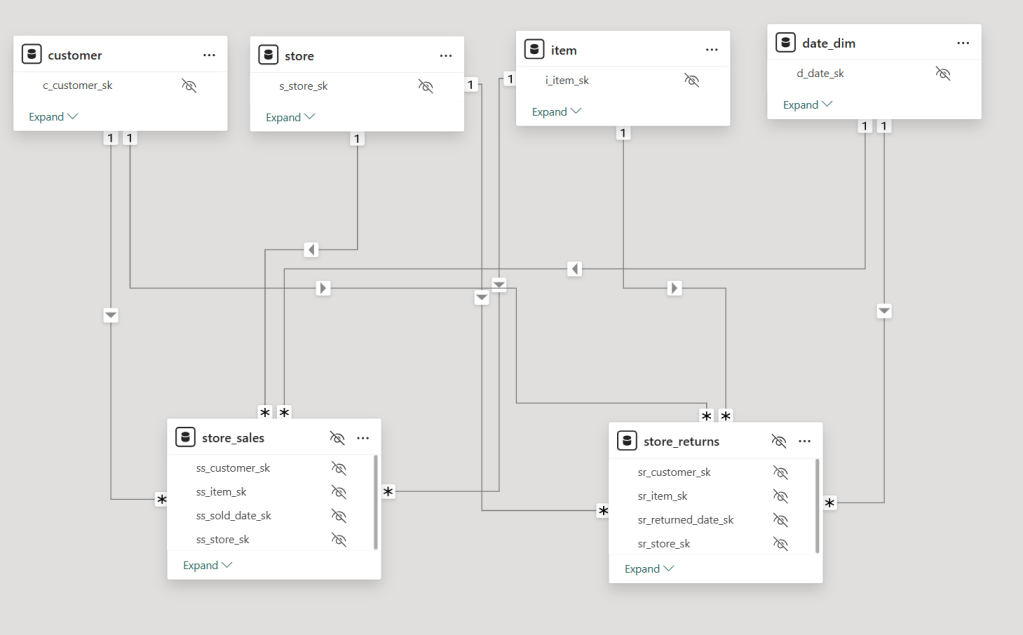

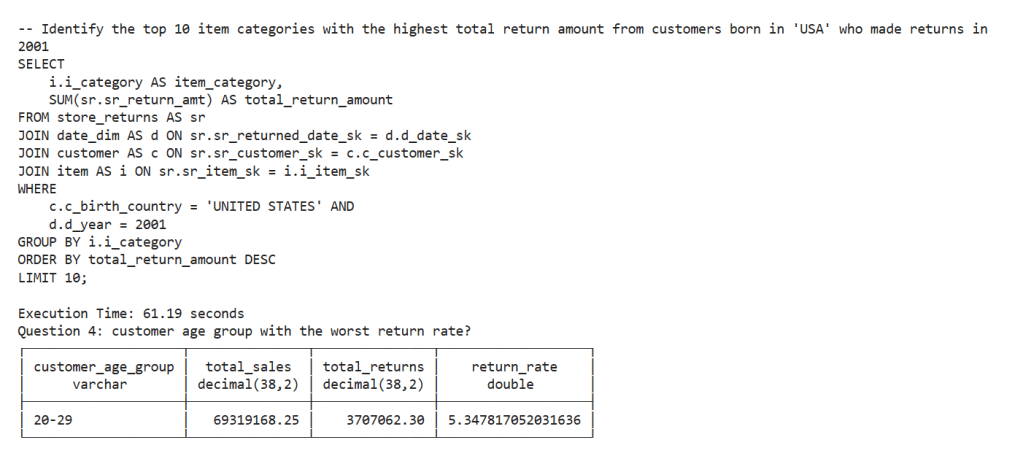

The experiment uses a SQL generation test based on the TPC-DS dataset (scale factor 0.1), featuring a star schema with two fact tables (store_sales, store_returns) and multiple dimension tables (date_dim, store, customer, item). The models were challenged with 20 questions ranging from simple aggregations to complex analytical queries requiring proper dimensional modeling techniques.

The Models Under Test

- O3-Mini (Reference Model): Cloud-based Azure model serving as the “ground truth”

- Qwen3-30B-A3B-2507: Local model via LM Studio

- GPT-OSS-20B : Local model via LM Studio

Usually I use Ollama, but moved to LM studio because of MCP tools support, for Qwen 3, strangely code did not perform well at all, and the thinking mode is simply too slow

Key Technical Constraints

- Memory Limit: Both local models run on 4GB VRAM, my laptop has 32 GB of RAM

- Timeout: 180 seconds per query

- Retry Logic: Up to 1 attempt for syntax error correction

- Validation: Results compared using value-based matching (exact, superset, subset)

The Testing Framework

The experiment employs a robust testing framework with several features:

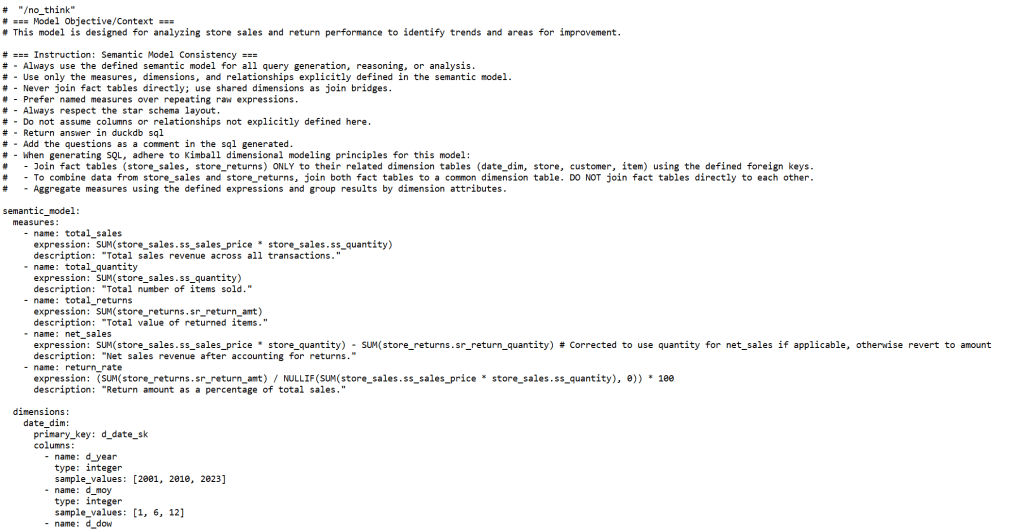

Semantic Model Enforcement

The models were provided with a detailed semantic model that explicitly defines:

- Proper dimensional modeling principles

- Forbidden patterns (direct fact-to-fact joins)

- Required CTE patterns for combining fact tables

- Specific measure definitions and business rules

Multi-Level Result Validation

Results are categorized into five match types:

- Exact Match: Identical results including order

- Superset: Model returns additional valid data

- Subset: Model returns partial but correct data

- Mismatch: Different results

- Error: Execution or generation failures

The Results: Not bad at all

Overall Performance Summary

Both local models achieved 75-85% accuracy, which is remarkable considering they’re running on consumer-grade hardware with just 4GB VRAM. The GPT-OSS-20B model slightly outperformed Qwen3 with 85% accuracy versus 75%. Although it is way slower

I guess we are not there yet for interactive use case, it is simply too slow for a local setup, specially for complex queries.

Tool calling

a more practical use case is tools calling, you can basically use it to interact with a DB or PowerBI using an mcp server and because it is totally local, you can go forward and read the data and do whatever you want as it is total isolated to your own computer.

The Future is bright

I don’t want to sounds negative, just 6 months ago, i could not make it to works at all, and now I have the choice between multiple vendors and it is all open source, I am very confident that those Models will get even more efficient with time.