This started as just a fun experiment. I was curious to see what happens when you push DuckDB really hard — like, absurdly hard. So I went straight for the biggest Python single-node compute we have in Microsoft Fabric: 64 cores and 512 GB of RAM. Because why not?

Setting Things Up

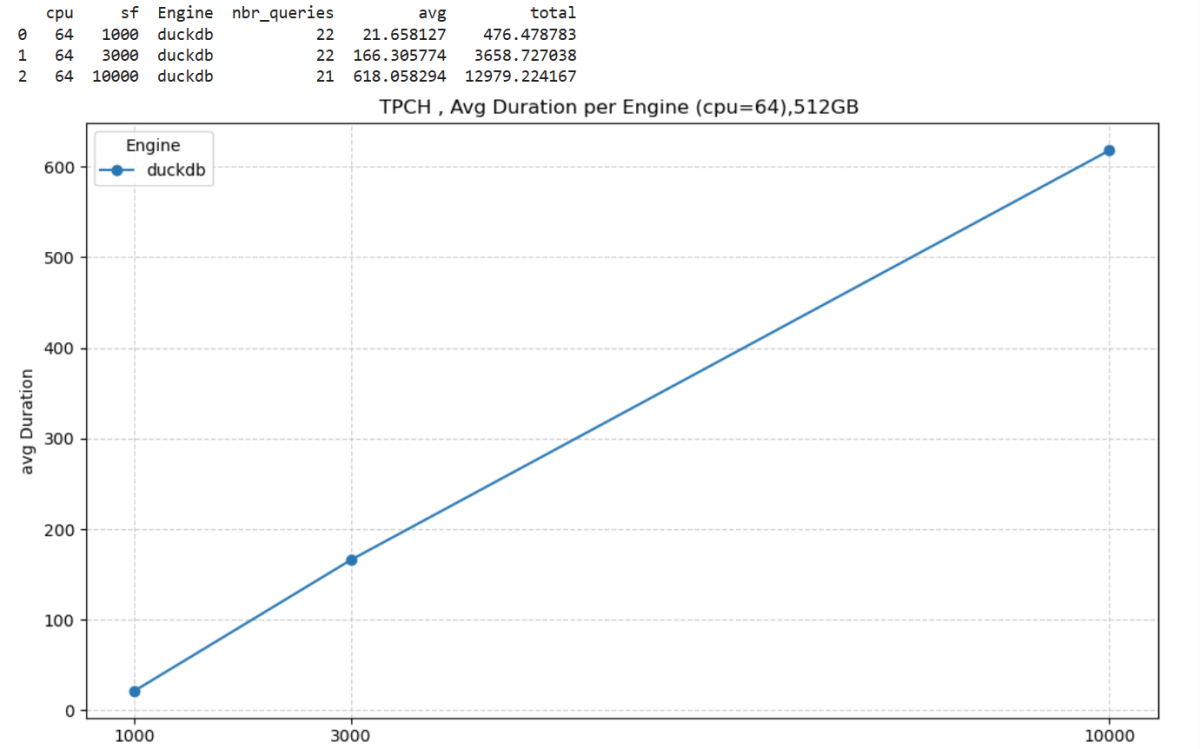

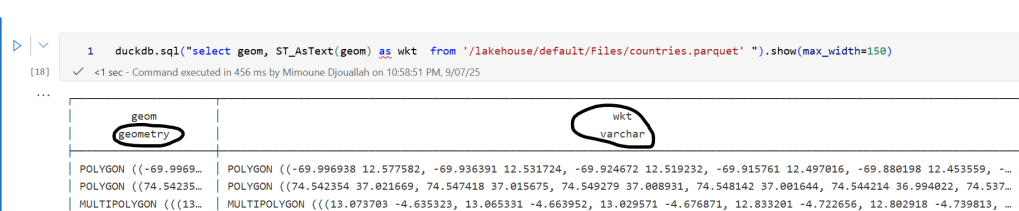

I generated data using tpchgen and registered it with delta_rs. Both are Rust-based tools, but I used their Python APIs (as it should be, of course). I created datasets at three different scales: 1 TB, 3 TB, and 10 TB.

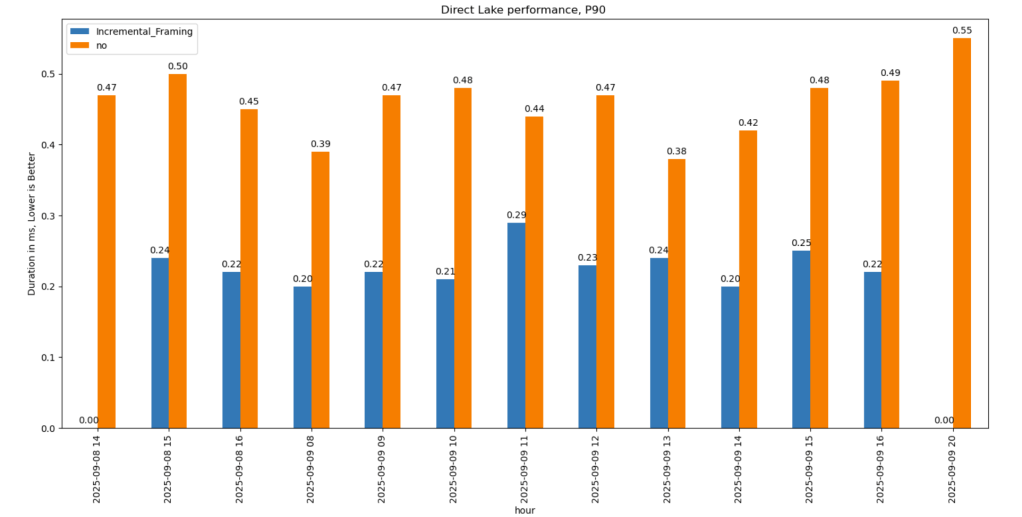

From previous tests, I know that Ducklake works better, but I used Delta so it is readable by other Fabric Engines ( as of this writing , Ducklake does not supporting exporting Iceberg metadata, which is unfortunate)

You can grab the notebook if you want to play with it yourself .

What I Actually Wanted to Know

The goal wasn’t really about performance . I wanted to see if it would work at all. DuckDB has a reputation for being great with smallish data, but wanted to see when the data is substantially bigger than the available Memory.

And yes, it turns out DuckDB can handle quite a bit more than most people assume.

The Big Lesson: Local Disk Matters

Here’s where things got interesting.

If you ever try this yourself, don’t use a Lakehouse folder for data spilling. It’s painfully slow(as the data is first written to disk then uploaded to remote storage)

Instead, point DuckDB to the local disk that Fabric uses for AzureFuse caching. That disk is about 2 TB. or any writable folder

You can tell DuckDB to use it like this:

SET temp_directory = '/mnt/notebookfusetmp';

Once I did that, I could actually see the data spilling happening in real time which felt oddly satisfying, it works but slow , it is better to just have more RAM 🙂

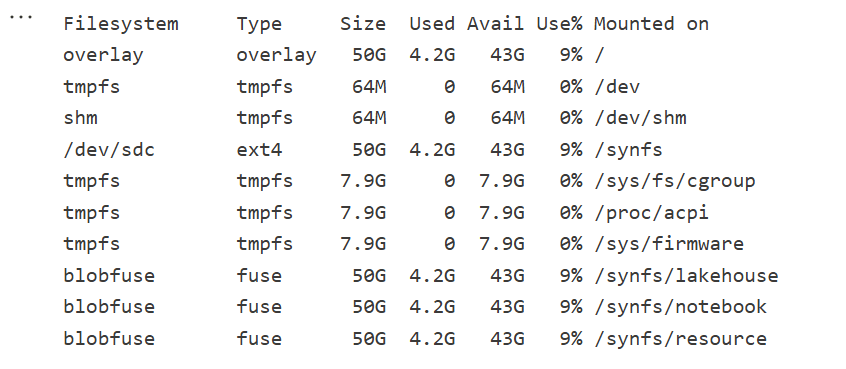

Python notebook is fundamentally just a Linux VM, and you can see the storage layout using this command

!df -hTHere is the layout for 2 cores

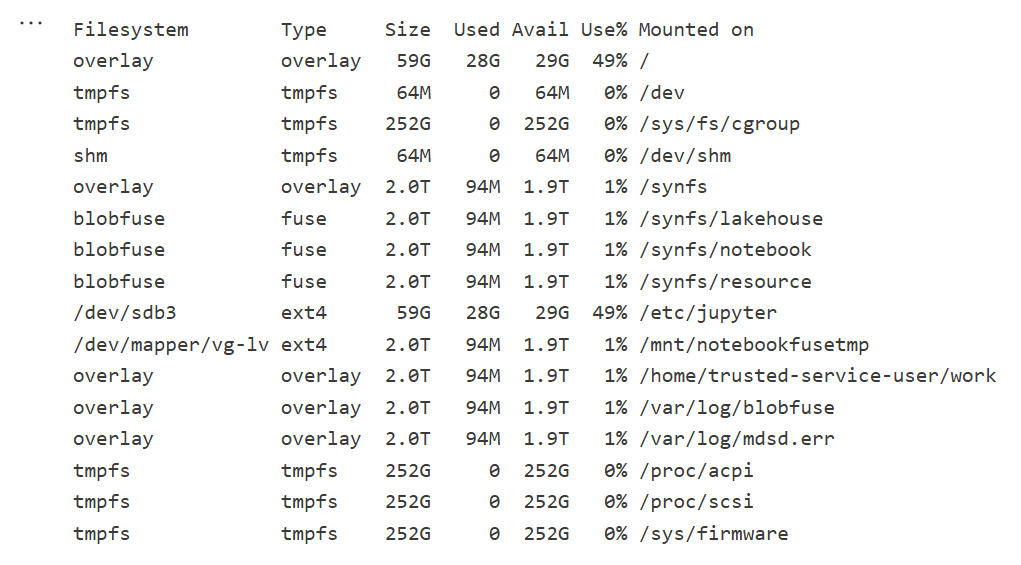

Which is different when running it for 64 cores ( container vs VM, something like that), I notice the local disk increased with more cores, which make sense

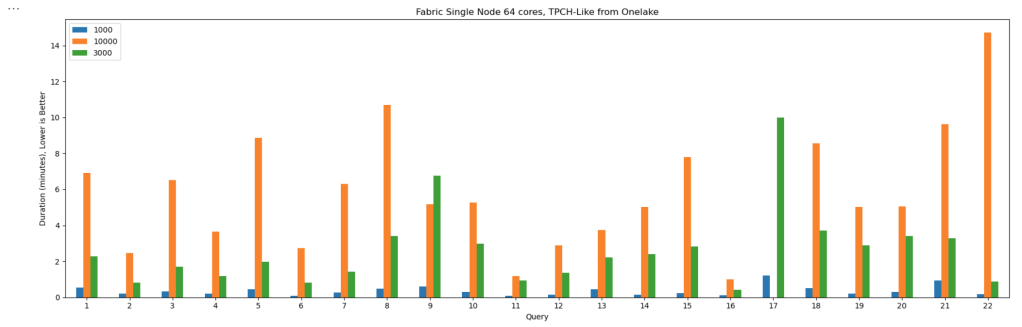

The Results

Most queries went through without too much trouble. except Query 17 at 10 TB scale? That one It ran for more than an hour before my authentication token expired. So technically, it didn’t fail 🙂

DuckDB does not have a way to refresh Azure token mid query. as far as I know

Edit : according to Claude, I need at least 1-2 TB of RAM (10-20% of database size) to avoid disk thrashing

Observations: DuckDB’s Buffer Pool

Something I hadn’t noticed before is how the buffer pool behaves when you work with data way bigger than your RAM. It tends to evict data that was just read from remote storage — which feels wasteful. I can’t help but think it might be better to spill that to disk instead.

I’m now testing an alternative cache manager called duck-read-cache-fs to see if it handles that better. We’ll see, i still think it is too low level to be handled by an extension, I know MotherDuck rewrote their own buffer manager, but not sure if it is for the same reason.

Why not test other Engines

I did, actually , and the best result I got was with Lakesail at around 100 GB. Beyond that, no single-node open-source engine can really handle this scale. Polars, for instance, doesn’t support spilling to disk at all and implements fewer than 10 of the 22 standard SQL queries.

Wrapping Up

So, what did I learn? DuckDB is tougher than it looks. With proper disk spilling and some patience, it can handle multi-terabyte datasets just fine, and sometimes the right solution is just to add more RAM

personally , I never had a need for TB of data ( my sweet spot is 100 GB) and distributed system (Like Fabric DWH, Spark etc) will handle this use case way better, after all they were designed for this scale.

But it’s amazing to see how far an in-process database has come 🙂 just a couple of years ago, I was thrilled when DcukDB could handle 10 GB!