🌟 Introduction

While testing the DuckDB ODBC driver, which is getting better and better (not production ready but less broken compared to two years ago), I noticed something unexpected. Running queries through Power BI in DirectQuery mode was actually faster than executing them directly in the DuckDB native UI.

Naturally, that does not make sense !!!

What followed was an investigation that turned into a fun and insightful deep dive into text-to-SQL generation, Power BI’s query behavior, and the enduring relevance of manual SQL tuning

🧩 The Goal: Find the Worst Product by Return Rate

The task was straightforward:

Calculate total sales, total returns, and return rate by product. Rank the products and find the top 5 with the highest return rates.

To make it interesting, I decided to try:

- Letting an LLM generate the SQL by loading the semantic model.

- Using PowerBI in Direct Query Mode.

- Finally, manually tuning the query.

📝 Step 1: LLM-generated SQL — Clean and Understandable

chatgpt generated a good starting point:

WITH sales_by_product AS (

SELECT

i.i_product_name AS product_name,

SUM(ss.ss_sales_price * ss.ss_quantity) AS total_sales

FROM store_sales ss

JOIN item i ON ss.ss_item_sk = i.i_item_sk

WHERE i.i_product_name IS NOT NULL

GROUP BY i.i_product_name

),

returns_by_product AS (

SELECT

i.i_product_name AS product_name,

SUM(sr.sr_return_amt) AS total_returns

FROM store_returns sr

JOIN item i ON sr.sr_item_sk = i.i_item_sk

WHERE i.i_product_name IS NOT NULL

GROUP BY i.i_product_name

),

combined AS (

SELECT

COALESCE(s.product_name, r.product_name) AS product_name,

COALESCE(s.total_sales, 0) AS total_sales,

COALESCE(r.total_returns, 0) AS total_returns

FROM sales_by_product s

FULL OUTER JOIN returns_by_product r

ON s.product_name = r.product_name

)

SELECT

product_name,

ROUND((total_returns / NULLIF(total_sales, 0)) * 100, 2) AS return_rate

FROM combined

WHERE total_sales > 0 -- Avoid divide by zero

ORDER BY return_rate DESC

limit 5 ;

✅ Pros:

- Clean and easy to read.

- Logically sound.

- Good for quick prototyping.

🔍 Observation: However, it used product_name (a text field) as the join key in the combined table, initially I was testing using TPC-DS10, the performance was good, but when I changed it to DS100, performance degraded very quickly!!! I should know better but did not notice that product_name has a lot of distinct values.

the sales table is nearly 300 M rows using my laptop, so it is not too bad

and it is nearly 26 GB of highly compressed data ( just to keep it in perspective)

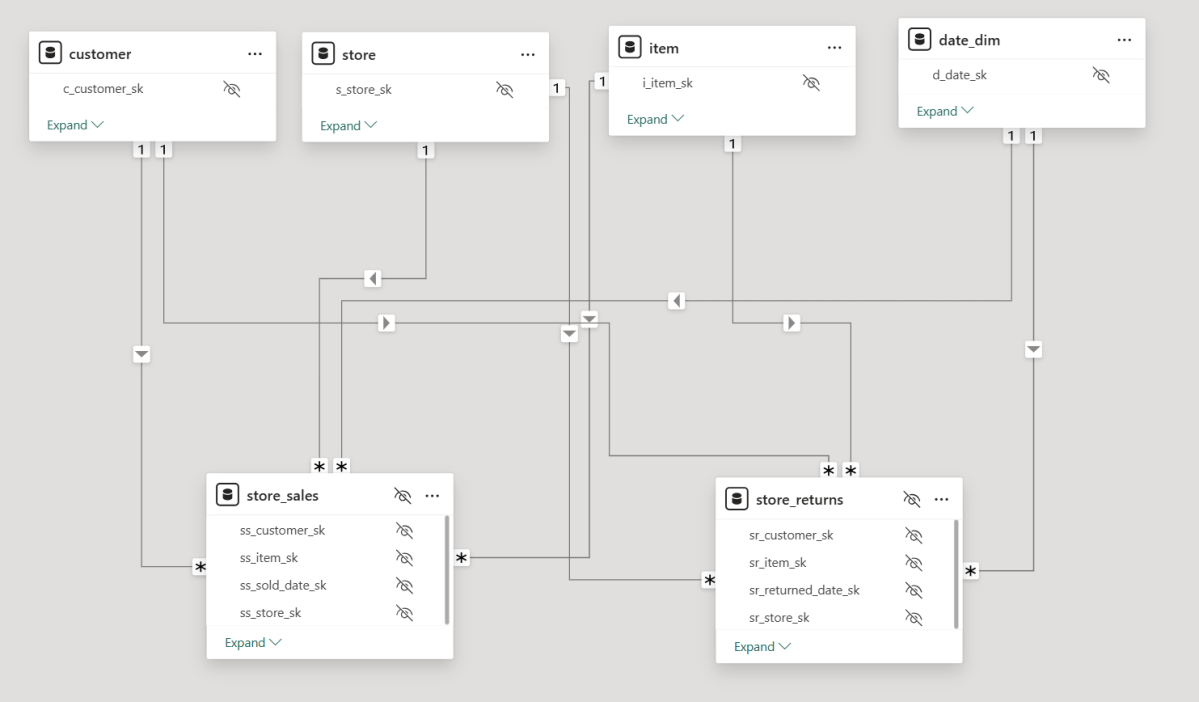

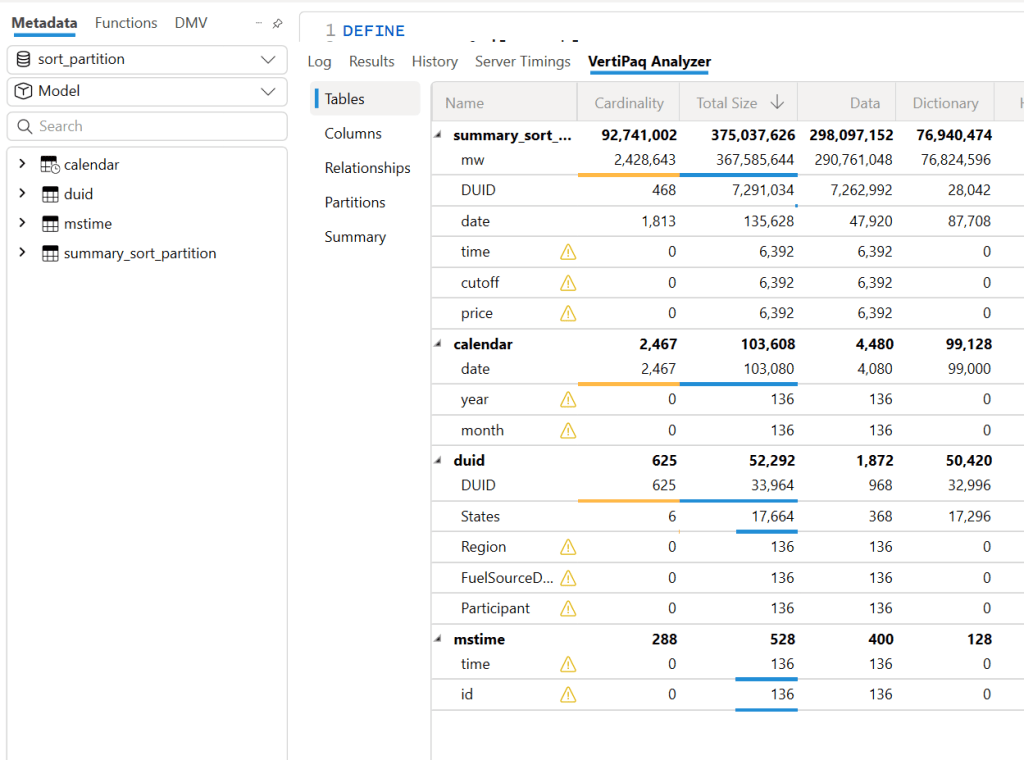

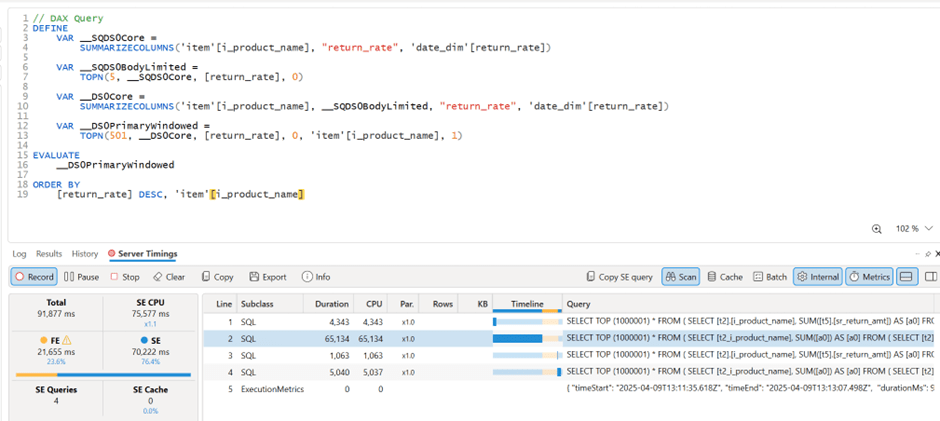

📊 Step 2: Power BI DirectQuery Surprises

Power BI automatically generate SQL Queries based on the Data Model, Basically you defined measures using DAX, you add a visual which generate a DAX query that got translated to SQL, based on some complex logic, it may or may not push just 1 query to the source system, anyway in this case, it did generated multiple SQL queries and stitched the result together.

🔍 Insight: Power BI worked exactly as designed:

- It split measures into independent queries.

- It grouped by

product_name, because that was the visible field in my model. - And surprisingly, it was faster than running the same query directly in DuckDB CLI!

Here’s my screenshot showing Power BI results and DAX Studio:

🧩 Step 3: DuckDB CLI — Slow with Text Joins

Running the same query directly in DuckDB CLI was noticeably slower, 290 seconds !!!

⚙️ Step 4: Manual SQL Tuning — Surrogate Keys Win

To fix this, I rewrote the SQL manually:

- Switched to

item_sk, a surrogate integer key. - Delayed lookup of human-readable fields.

Here’s the optimized query:

WITH sales_by_product AS (

SELECT

ss.ss_item_sk AS item_sk,

SUM(ss.ss_sales_price * ss.ss_quantity) AS total_sales

FROM store_sales ss

GROUP BY ss.ss_item_sk

),

returns_by_product AS (

SELECT

sr.sr_item_sk AS item_sk,

SUM(sr.sr_return_amt) AS total_returns

FROM store_returns sr

GROUP BY sr.sr_item_sk

),

combined AS (

SELECT

COALESCE(s.item_sk, r.item_sk) AS item_sk,

COALESCE(s.total_sales, 0) AS total_sales,

COALESCE(r.total_returns, 0) AS total_returns

FROM sales_by_product s

FULL OUTER JOIN returns_by_product r ON s.item_sk = r.item_sk

)

SELECT

i.i_product_name AS product_name,

ROUND((combined.total_returns / NULLIF(combined.total_sales, 0)) * 100, 2) AS return_rate

FROM combined

LEFT JOIN item i ON combined.item_sk = i.i_item_sk

WHERE i.i_product_name IS NOT NULL

ORDER BY return_rate DESC

LIMIT 5;

🚀 Result: Huge performance gain! from 290 seconds to 41 seconds

Check out the improved runtime in DuckDB CLI:

🌍 In real-world models, surrogate keys aren’t typically used

unfortunately in real life, people still use text as a join key, luckily PowerBI seems to do better there !!!

🚀 Final Thoughts

LLMs are funny, when I asked chatgpt why it did not suggest a better SQL Query, I got this answer 🙂

I guess the takeaway is this:

If you’re writing SQL queries, always prefer integer types for your keys!

And maybe, just maybe, DuckDB (and databases in general) could get even better at optimizing joins on text columns. 😉

But perhaps the most interesting question is:

What if, one day, LLMs not only generate correct SQL queries but also fully performance-optimized ones?

Now that would be exciting.

you can download the data here, it is using very small factor : https://github.com/djouallah/Fabric_Notebooks_Demo/tree/main/SemanticModel

Edit : run explain analyze show that it is group by is taking most of the time and not the joins

the optimized query assumed already that i.i_item_sk is unique, it is not very obvious for duckdb to rewrite the query without knowing the type of joins !!! I guess LLMs still have a lot to learn