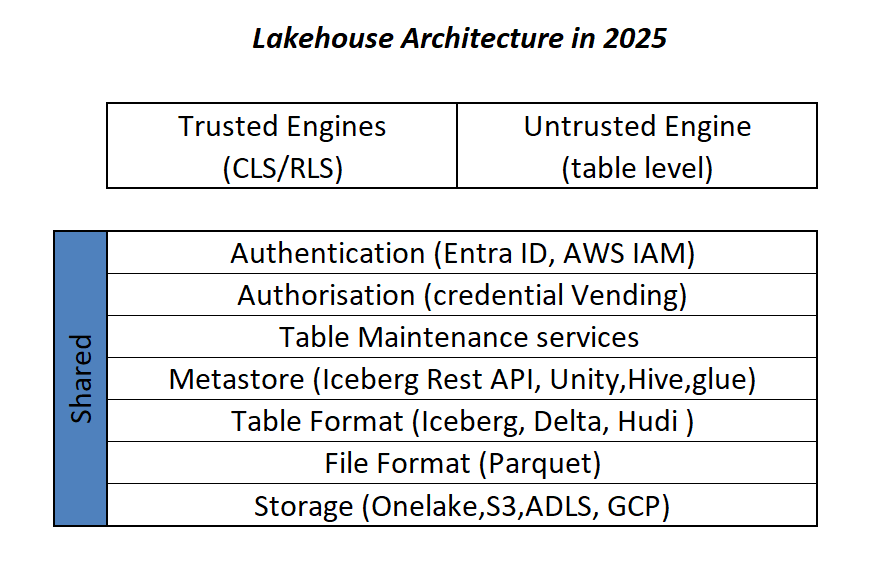

I know it is a niche topic, and in theory, we should not think about it. in import mode, Power BI ingests data and automatically optimizes the format without users knowing anything about it. With Direct Lake, it has become a little more nuanced. The ingestion part is done downstream by other processes that Power BI cannot control. The idea is that if your Parquet files are optimally written using Vorder, you will get the best performance. The reality is a bit more complicated. External writers know nothing about Vorder, and even some internal Fabric Engines do not write it by default.

To show the impact of read performance for Vordered Parquet vs sorted Parquet, I ran some tests. I spent a lot of time ensuring I was not hitting the hot cache, which would defeat the purpose. One thing I learned is to test only one aspect of the system carefully.

Cold Run: Data loaded from OneLake with on-the-fly building of dictionaries, relationships, etc

Warm Run: Data already in memory format.

Hot Run: The system has already scanned the same data before. You can disable this by calling the ClearCache command using XMLA (you cannot use a REST API call).

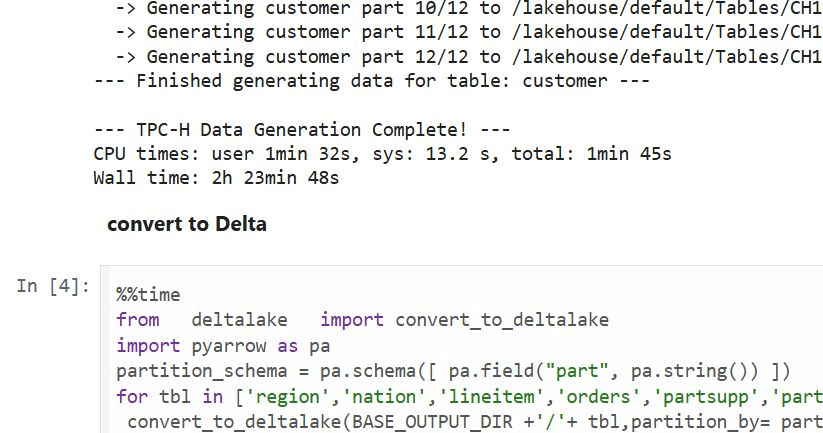

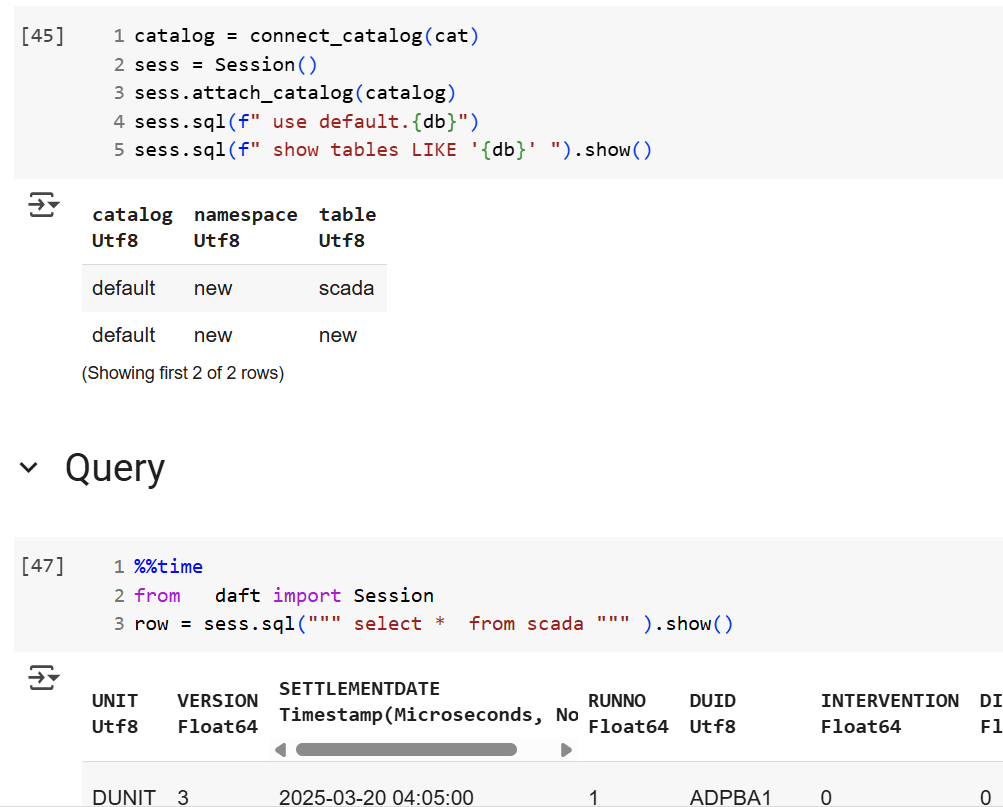

Prepare the Data

Same model, three dimensions, and one fact table, you can generate the data using this notebook

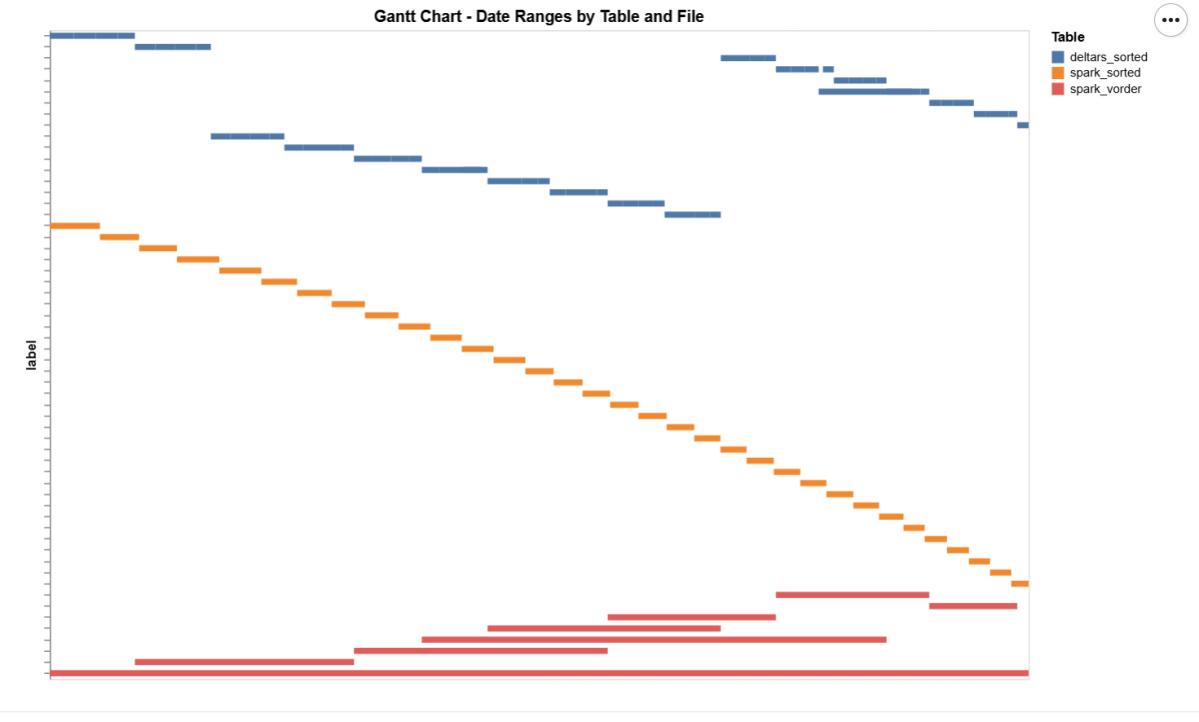

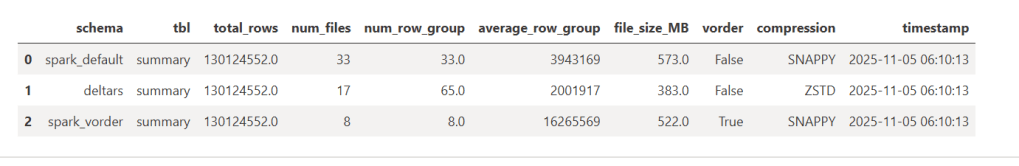

- Deltars: Data prepared using Delta Rust sorted by

date,id, thentime. - Spark_default: Same sorted data but written by Spark.

- Spark_vorder: Manually enabling Vorder (Vorder is off by default for new workspaces).

Note: you can not sort and vorder at the same time, at least in Spark, DWH seems to support it just fine

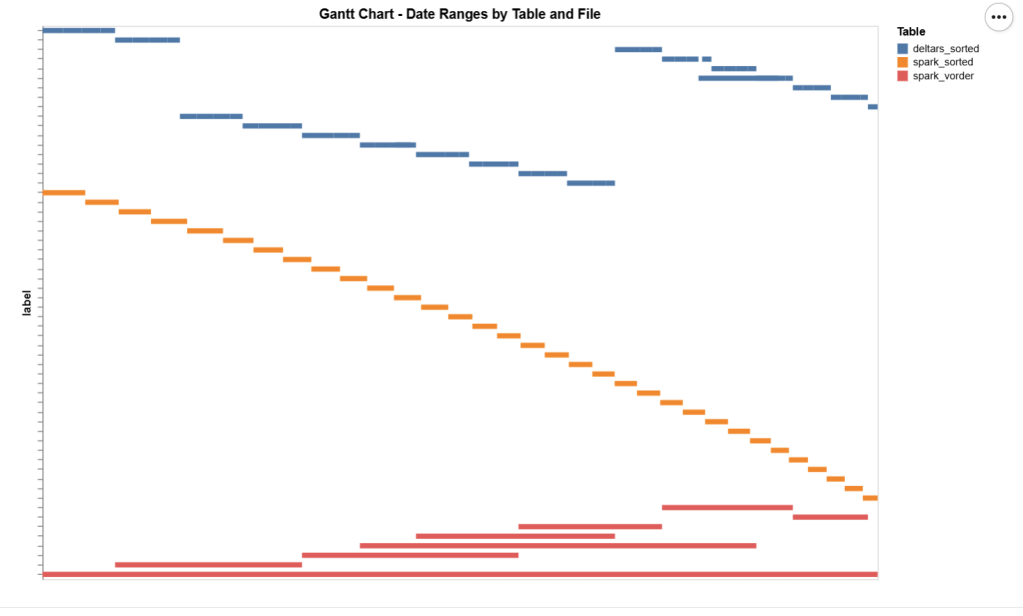

The data layout is as follows:

I could not make Delta Rust produce larger row groups. Notice that ZSTD gives better compression, although it seems Power BI has to uncompress the data in memory, so it seems it is not a big deal

I added a bar chart to show how the data is sorted per date. As expected, Vorder is all over the place, the algorithm determines that this is the best row reordering to achieve the best RLE encoding.

The Queries

The queries are very simple. Initially, I tried more complex queries, but they involved other parts of the system and introduced more variables. I was mainly interested in testing the scan performance of VertiPaq.

Basically, it is a simple filter and aggregation.

The Test

You can download the notebook here :

def run_test(workspace, model_to_test):

for i, dataset in enumerate(model_to_test):

try:

print(dataset)

duckrun.connect(f"{ws}/{lh}.Lakehouse/{dataset}").deploy(bim_url)

run_dax(workspace, dataset, 0, 1)

time.sleep(300)

run_dax(workspace, dataset, 1, 5)

time.sleep(300)

except Exception as e:

print(f"Error: {e}")

return 'done'

Deploy automatically generates a new semantic model. If it already exists, it will call clearvalue and perform a full refresh, ensuring no data is kept in memory. When running DAX, I make sure ClearCache is called.

The first run includes only one query; the second run includes five different queries. I added a 5-minute wait time to create a clearer chart of capacity usage.

Capacity Usage

To be clear, this is not a general statement, but at least in this particular case with this specific dataset, the biggest impact of Vorder seems to appear in the capacity consumption during the cold run. In other words:

Transcoding a vanilla Parquet file consumes more compute than a Vordered Parquet file.

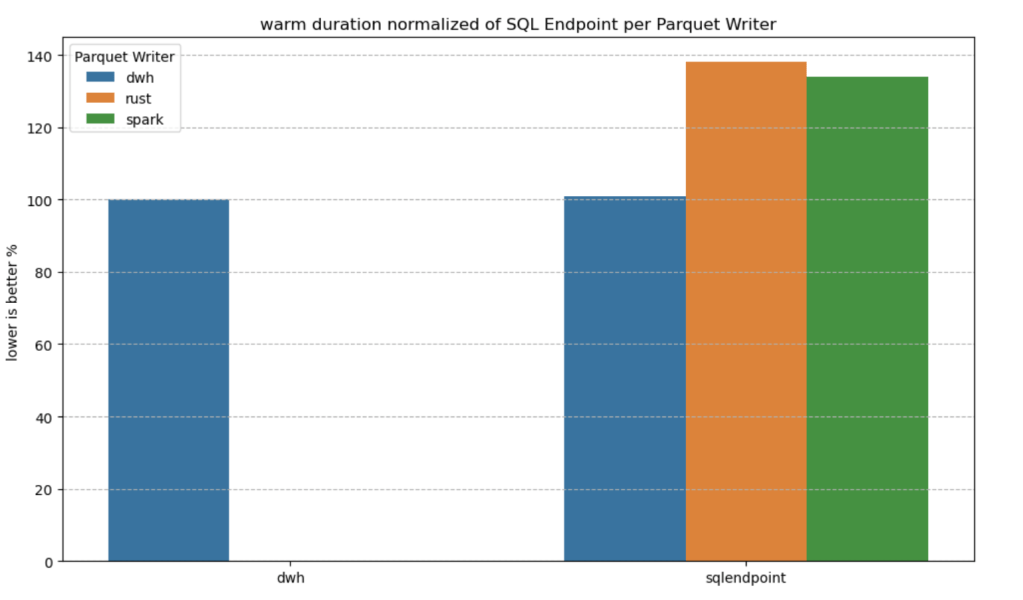

Warm runs appear to be roughly similar.

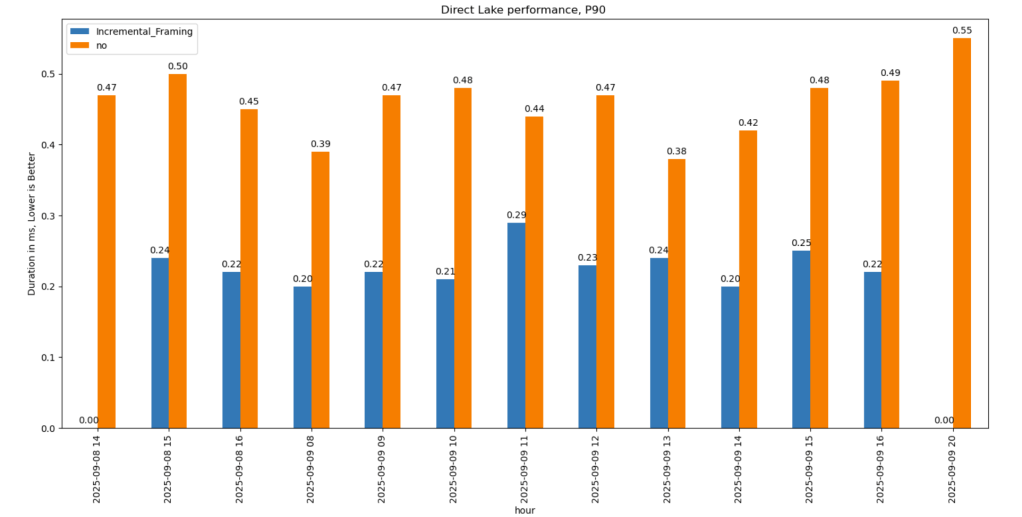

Impact on Performance

Again, this is based on only a couple of queries, but overall, the sorted data seems slightly faster in warm runs (although more expensive). Still, 120 ms vs 340 ms will not make a big difference. I suspect the queries I ran aligned more closely with the column sorting—that was not intentional.

Takeaway

Just Vorder if you can. Make sure you enable it when starting a new project. ETL, data engineering have only one purpose, make the experience of the end users the best possible way, ETL job that take 30 seconds more is nothing compared to a slower PowerBI reports.

now if you can’t, maybe you are using a shortcut from an external engine, check your powerbi performance if it is not as good as you expect then make a copy, the only thing that matter is the end user experience.

Another lesson is that VertiPaq is not your typical OLAP engine; common database tricks do not apply here. It is a unique engine that operates entirely on compressed data. Better-RLE encoded Parquet will give you better results, yes you may have cases where the sorting align better with your queries pattern, but in the general case, Vorder is always the simplest option.