This is not an official benchmark—just an exercise to experiment with the new Fabric Python notebook.

You can download the notebook and the results here

There is a growing belief that most structured data will eventually be stored in an open table format within object stores, with users leveraging various engines to query that data. The idea of data being tied to a specific data warehouse (DWH) may soon seem absurd, as everything becomes more open and interoperable.

While I can’t predict the future, 2024 will likely be remembered as the year when the lakehouse concept decoupled from Spark. It has become increasingly common for “traditional” DWHs or any Database for that matter to support open table formats out of the box. Fabric DWH, for instance, uses a native storage layer based on Parquet and publishes Delta tables for consumption by other engines. Snowflake now supports Iceberg, and BigQuery is slowly adding support as well.

I’m not particularly worried about those DWH engines—they have thousands of engineers and ample resources, they will be doing just fine.

My interest lies more in the state of open source Python engines, such as Polars and DataFusion, and how they behave with a limited resource environment.

Benchmarking Bias

Any test inherently involves bias, whether conscious or unconscious. For interactive queries, SQL is the right choice for me. I’m aware of the various DataFrame APIs, but I’m not inclined to learn a new API solely for testing. For OLAP-type queries, TPC-DS and TPC-H are the two main benchmarks. This time, I chose TPC-DS for reasons explained later.

Benchmark Setup

All data is stored in OneLake’s Melbourne region, approximately 1,400 km away from my location, the code will check if the data exists otherwise it will be generated, the whole thing is fully reproducible.

I ran each query only once, ensuring that the DuckDB cache, which is temporary, was cleared between sessions. This ensures a fair comparison.

I explicitly used the smallest available hardware since larger setups could mask bottlenecks. Additionally, I have a specific interest in the Fabric F2 SKU.

While any Python library can be used, as of this writing, only two libraries—DuckDB and DataFusion—support:

- Running the 99 TPC-DS queries (DataFusion supports 95, which is sufficient for me).

- Native Delta reads for

abfssor at least local paths. - Python APIs, as they are required to run queries in a notebook.

Other libraries like ClickHouse, Databend, Daft, and Polars lack either mature Delta support or compatibility with complex SQL benchmarks like TPC-DS.

Why TPC-DS ?

TPC-DS presents a significantly greater challenge than TPC-H, with 99 queries compared to TPC-H’s 22. Its more complex schema, featuring multiple fact and dimension tables, provides a richer and more demanding testing environment.

Why 10GB?

The 10GB dataset reflects the type of data I encountered as a Power BI developer. My focus is more on scaling down than scaling up. For context:

- The largest table contains 133 million rows.

- The largest table by size is 1.1GB.

Admittedly, TPC-DS 10GB is overkill since my daily workload was around 1GB. However, running it on 2 cores and 16GB of RAM highlights DuckDB’s engineering capabilities.

btw, I did run the same test using 100GB and the python notebook with 16 GB did works just fine, but it took 45 minutes.

OneLake Access Modes

You can query OneLake using either abfss or mounted storage. I prefer the latter, as it simulates a local path and libraries don’t require authentication or knowledge of abfss. Moreover, it caches data on runtime SSDs, which is an order of magnitude faster than reading from remote storage. Transactions are also included in the base capacity unit consumption, eliminating extra OneLake costs.

It’s worth noting that disk storage in Fabric notebook is volatile and only available during the session, while OneLake provides permanent storage.

You can read more about how to laverage DuckDB native storage format as a cache layer here

Onelake Open internet throughput

My internet connection is not too bad but not great either, I managed to get a peak of 113 Mbps, notice here the extra compute of my laptop will not help much as the bottleneck is network access.

Results

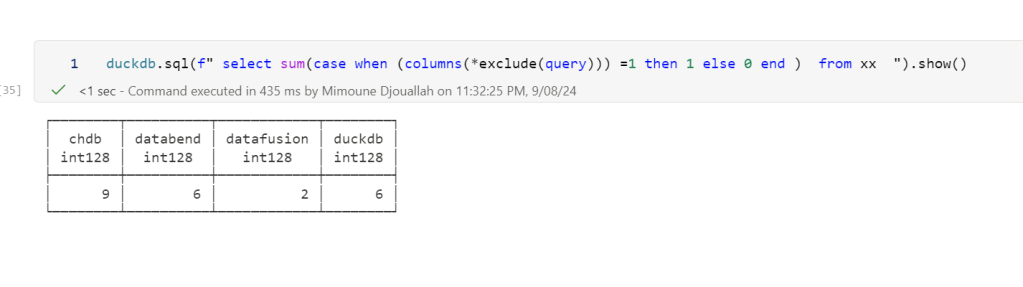

The table below summarizes the results across different modes, running both in Fabric notebooks and on my laptop.

- DuckDB Disk caching yielded the shortest durations but the worst individual query performance, as copying large tables to disk takes time.

- Delta_rs SQL performance was somewhat erratic.

- Performance on my laptop was significantly slower, influenced by my internet connection speed.

- Mounted storage offered the best overall experience, caching only the Parquet files needed for queries.

And here is the geomean

Key Takeaways

- For optimal read performance, use mounted storage.

- For write operations, use the

abfsspath. - Having a data center next to your laptop is probably a very good idea 🙂

Due to network traffic, Querying inside the same region will be faster than Querying from the web (I know, it is a pretty obvious observation)

but is Onelake throughput good ?

I guess that’s the core question, to answer that I changed the Python notebook to use 8 cores, and run the test from my laptop using the same data stored in my SSD Disk, no call to onelake, and the results are just weird

Reading from Onelake using mounted storage in Fabric Notebook is faster than reading the same data from my Laptop !!!!

Looking Ahead to 2025

2024 has been an incredible year for Python engines, evolving from curiosities to tools supported by major vendors. However, as of today, no single Python library supports disk caching for remote storage queries. This remains a gap, and I hope it’s addressed in 2025.

For Polars and Daft, seriously works on better SQL support