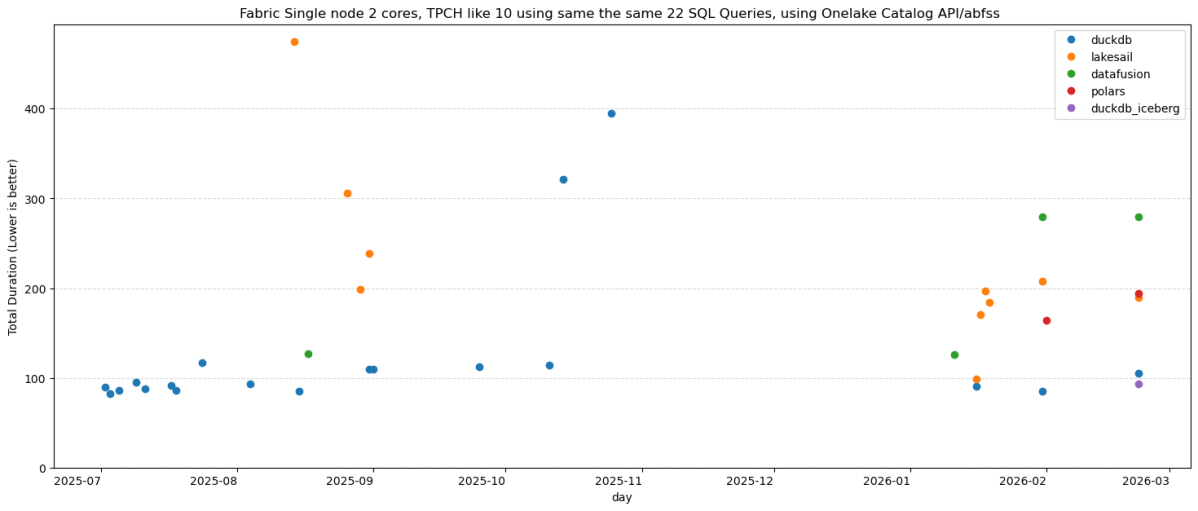

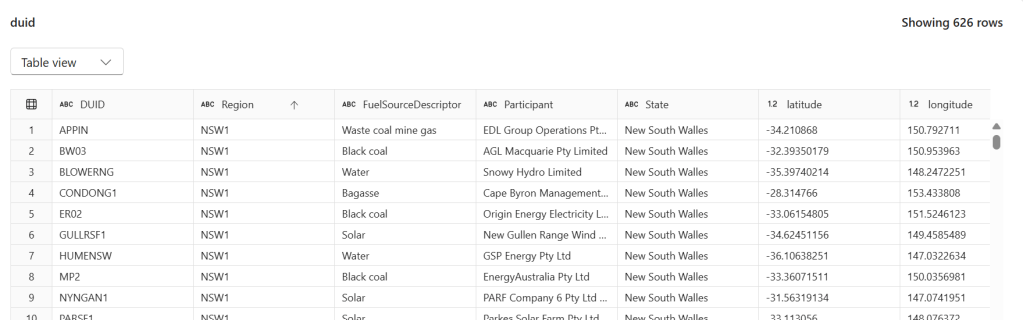

Same 22 TPC-H queries. Same Delta Lake data on OneLake (SF10). Same single Fabric node. Five Python SQL engines: DuckDB (Delta Classic), DuckDB (Iceberg REST), LakeSail, Polars, DataFusion , you can download the notebook here

unfortunately both daft and chdb did not support reading from Onelake abfss

DuckDB iceberg read support is not new, but it is very slow, but the next version 1.5 made a massive improvements and now it is slightly faster than Delta

They all run the same SQL now

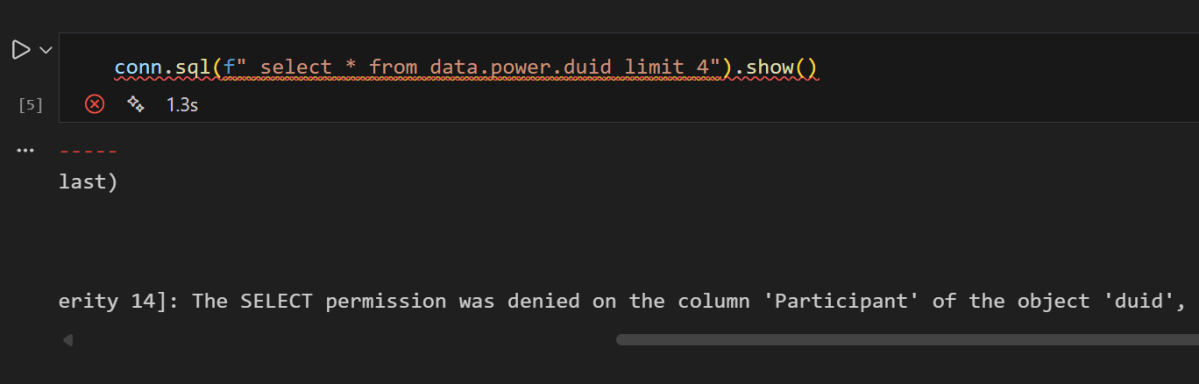

All five engines executed the exact same SQL. No dialect tweaks, no rewrites. The one exception: Polars failed on Query 11 with

`SQLSyntaxError: subquery comparisons with '>' are not supported` Everything else just worked,SQL compatibility across Python engines is basically solved in 2026. The differentiators are elsewhere.

Freshness vs. performance is a trade-off you should be making

import duckdbconn = duckdb.connect()conn.sql(f""" install delta_classic FROM community ;attach 'abfss://{ws}@onelake.dfs.fabric.microsoft.com/{lh}.Lakehouse/Tables/{schema}'AS db (TYPE delta_classic, PIN_SNAPSHOT); USE db """)`MAX_TABLE_STALENESS ‘5 minutes’` means the engine caches the catalog metadata and skips the round-trip for 5 minutes.

DuckDB’s Delta Classic does the same with `PIN_SNAPSHOT`.

import duckdbconn = duckdb.connect()conn.sql(f""" install delta_classic FROM community ;attach 'abfss://{ws}@onelake.dfs.fabric.microsoft.com/{lh}.Lakehouse/Tables/{schema}'AS db (TYPE delta_classic, PIN_SNAPSHOT); USE db """)Your dashboard doesn’t need sub-second freshness. Your reporting query doesn’t care about the last 30 seconds of ingestion. Declaring a staleness budget upfront – predictable, explicit – is not a compromise. It’s the right default for analytics.

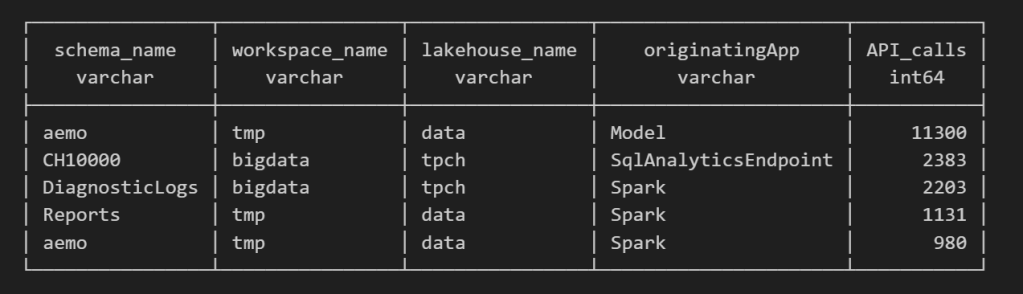

Object store calls are the real bottleneck

Every engine reads from OneLake over ABFSS. Every Parquet file is a network call. It doesn’t matter how fast your engine scans columnar data in memory if it makes hundreds of HTTP calls to list files and read metadata before it starts.

– DuckDB Delta Classic (PIN_SNAPSHOT): caches the Delta log and file list at attach time. Subsequent queries skip the metadata round-trips.

– DuckDB Iceberg (MAX_TABLE_STALENESS): caches the Iceberg snapshot from the catalog API. Within the staleness window, no catalog calls.

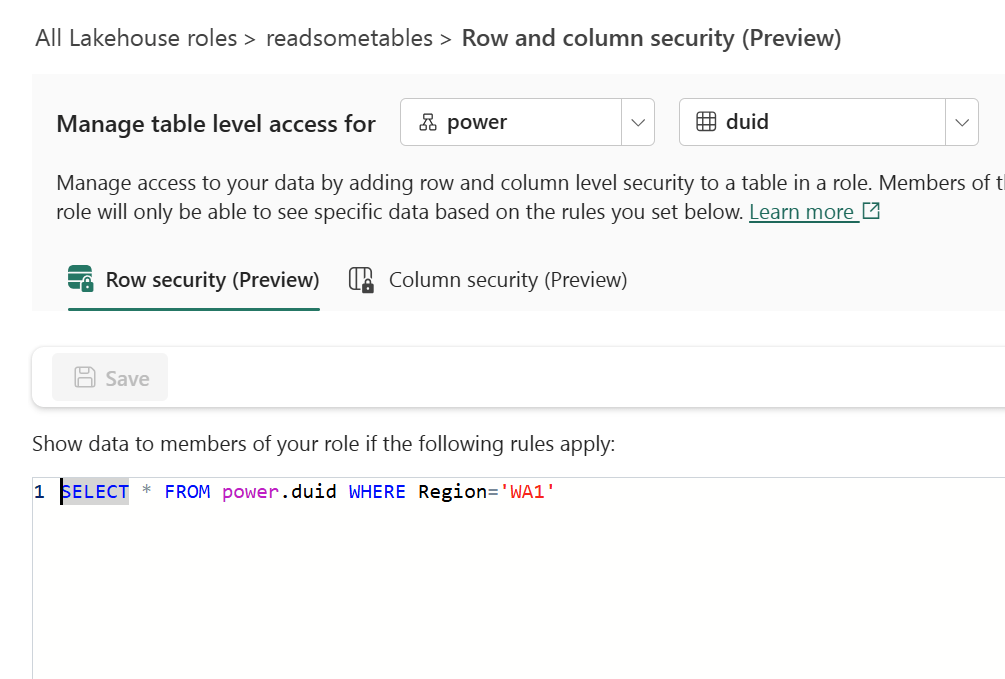

– LakeSail: has native OneLake catalog integration (SAIL_CATALOG__LIST). You point it at the lakehouse, it discovers tables and schemas through the catalog. Metadata resolution is handled by the catalog layer, not by scanning storage paths, but it has no concept of cache, every query will call Onelake Catalog API

– Polars, DataFusion: resolve the Delta log on every query. Every query pays the metadata tax.

An engine that caches metadata will beat a “faster” engine that doesn’t. Every time, especially at scale.

How about writes?

You can write to OneLake today using Python deltalake or pyiceberg – that works fine. But native SQL writes (CREATE TABLE AS INSERT INTO ) through the engine catalog integration itself? That’s still the gap, lakesail can write delta just fine but using a path.

– LakeSail and DuckDB Iceberg both depend on OneLake’s catalog adding write support. The read path works through the catalog API, but there’s no write path yet. When it lands, both engines get writes for free.

– DuckDB Delta Classic has a different bottleneck: DuckDB’s Delta extension itself. Write support exists but is experimental and not usable for production workloads yet.

The bottom line

Raw execution speed will converge. These are all open source projects, developers read each other’s code, there’s no magical trick one has that others can’t adopt. The gap narrows with every release.

Catalog Integration and cache are the real differentiator. And I’d argue that even *reading* from OneLake is nearly solved now.

—

Full disclosure: I authored the DuckDB Delta Classic extension and the LakeSail OneLake integration (both with the help of AI), so take my enthusiasm for catalog integration with a grain of bias